Zoom

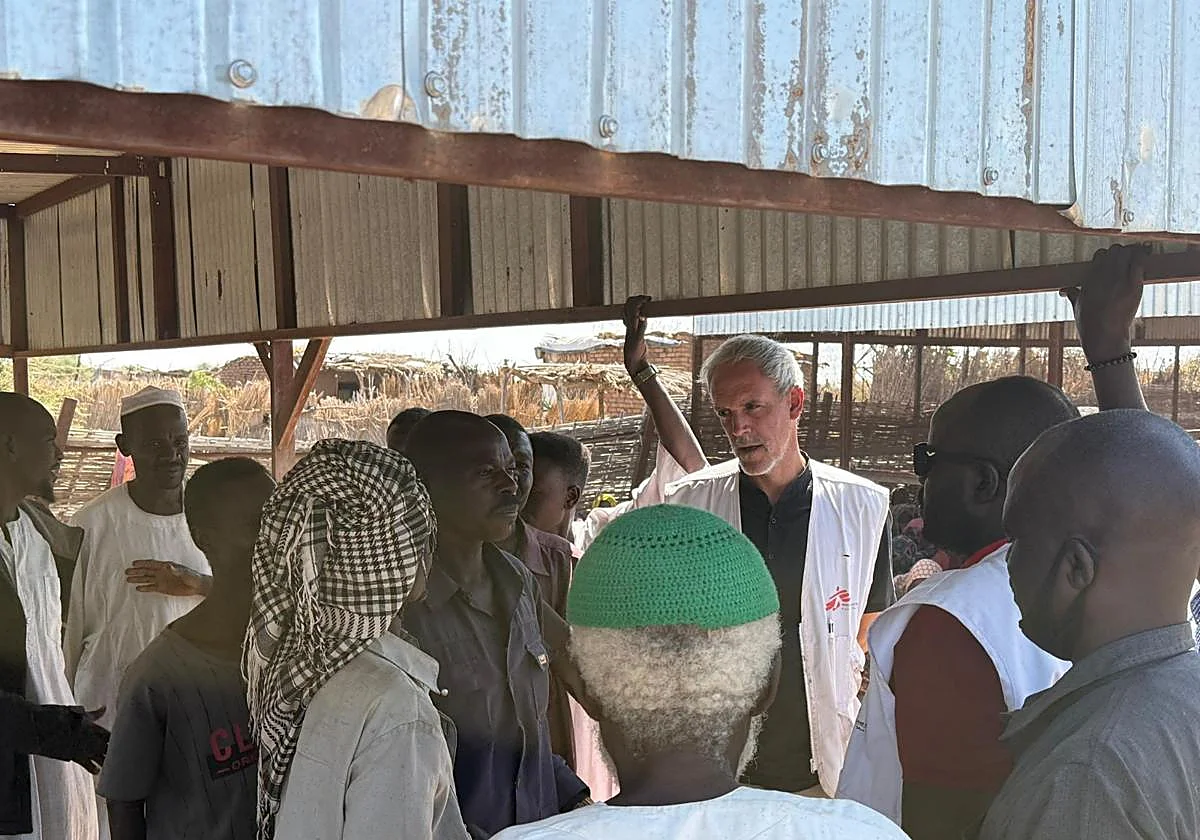

José Sánchez, working in Sudan. SUR Health A Ronda man amid Sudan's humanitarian crisis: 'I cannot see myself going back to a hospital in Europe'From Andalucía to Africa: José Sánchez is from Ronda, but has been working for Médecins Sans Frontières since 2010. He is currently in Africa, in one of the world's forgotten conflicts

Wednesday, 31 December 2025, 13:27

The news cycle is sometimes perverse: the wars that receive the most media coverage are those that are closest to home and whose causes are easiest to understand. Others, though equally or even more savage, are sometimes forgotten. José Sánchez, as medical coordinator in the emergency treatment unit of Médecins Sans Frontières (doctors without borders), has been through more than one type of conflict or another. Now he's dealing with one of those that barely catches a few lines in the newspapers or a few seconds on the news channels because of its remoteness and complexity: the Sudanese conflict.

Born in Ronda and a trained nurse, he belongs to a generation of healthcare professionals from Spain who packed their bags in search of a life with better working conditions. While some moved to Portugal or Italy, he chose France. He left for six months, which ended up being eight years. One Christmas, in 2009, changed his destiny. It happened at an airport. There he met a former classmate who worked for Médecins Sans Frontières. He told Sánchez that they were looking for people who spoke French. He had little experience in humanitarian work, beyond a few summers volunteering with the Red Cross, but he had almost a decade of professional experience in healthcare, essential for getting involved in an NGO mission. So, in 2010, he joined MSF and his first assignment was in Niger, where he worked on projects combating malnutrition, which formed a deadly combination with malaria.

"When I returned each morning, I found that ten to 15 children had died during the night. I had never seen a child die on my watch. I was left with the ones who'd survived and with the thought that, without us, more would die," he says.

The harsh reality of the work explains why only half of the people who start with Médecins Sans Frontières return after their first mission and only 20% to 30% of those who go on a 3rd or 4th mission stay. José Sánchez is one of those who have stayed: "I don't see myself going back to a health centre or hospital in Europe," he says. He wants to contribute to the populations of those countries that lack access to healthcare.

Still, his dedication to others takes its toll: "I have my parents, my siblings, my nieces, but I don't have a family of my own. Choosing this life means giving up many things, not being close to your loved ones in happy or sad times, but the work I do makes it all worthwhile."

"I don't regard myself as a hero. I see what I do as the work of a healthcare professional"

Nevertheless, he plays down the heroic nature of his work: "I don't regard myself as a hero. I see what I do as the work of a healthcare professional. You don't just have to work in hospitals, nurses can have other jobs: from providing training to direct bedside support with patients, and here I can do it all, because we train local staff, treat the sick, coordinate activities, carry out vaccination campaigns... and things that weren't even considered in my previous jobs. That's very fulfilling for me."

Working under fire

The performance of these responsibilities must be adapted to the situation, to the circumstances of the location where the mission takes place, because it might be in a context of active war, as in Gaza or Ukraine, where security surveillance is added to daily duties. It might be in the aftermath of an earthquake, like the one that devastated eastern Turkey, where José Sánchez's work took place in tents. Alternatively, the task might consist of carrying out measles vaccination campaigns, as he did in the Central African Republic or the Congo, where epidemics also have to be dealt with, reaching isolated places and setting up the necessary infrastructure to be as close as possible to the people needing treatment and care.

"We adapt to the context, to being under fire or to setting up vaccination campaigns on the beach using boats," he explains. Even adapting to a pandemic, as happened during a support mission to Venezuela so that healthcare services could reach the most isolated communities.

ZoomSo, now he is in Sudan, where a civil war broke out in 2023 between the government army and the Rapid Support Forces. "It is considered one of the world's biggest humanitarian crises. The UN says more than 30 million people are in need of assistance. There are 12 million internally displaced people, almost four million refugees in neighbouring states and tens of thousands of dead. Hospitals, health centres and healthcare workers have been attacked. Although there are many humanitarian organisations in the country, there are still unmet needs," explains Sanchez.

"We maintain our neutrality and impartiality. What we want is for people to have access to healthcare because, once again, there are cholera and measles epidemics"

Médecins Sans Frontières works in a divided state and operates both in government-controlled territories and in areas under the control of the Rapid Support Forces: "We maintain our neutrality and impartiality. What we want is for people to have access to healthcare because, once again, there are cholera and measles epidemics: routine vaccination was already inadequate before the war and now the situation has worsened", he continues.

Thousands displaced

When Sánchez spoke with SUR, he had just visited several of the organisation's projects in Sudan. For example, in Tawila, a city already hosting over 600,000 displaced people and where some 10,000 more have arrived in the last two months. Many of these displaced people have been on the move for months, fleeing the advance or retreat of the conflict and settling wherever they could, often in the middle of nowhere, in dry areas, in the desert, with limited access to water and no sanitation or healthcare facilities. "Since there is no government, no grassroots social structure, everyone depends on humanitarian aid: for water, for food, for plastic sheeting to protect themselves during the rainy season... for everything," he says.

Zoom"We are identifying women who have been raped even when they were looking for a safe place"

In a war zone, in a forgotten conflict, Sánchez coordinates a team that supports Sudanese hospitals and health centres, that has agents in isolated communities, that treats malaria and malnutrition and that provides for operating room coverage for emergencies such as appendicitis, C-sections and gunshot wounds.

They also distribute drinking water and build latrines. In short, they provide support in a barbaric reality where everyone has been a victim of violence, including sexual violence: "We are identifying women who have been raped even when they were looking for a safe place."

Many people have witnessed mass executions. Everyone has family members who have died in this war. So they also need mental health support, which is covered, not through individualised activities because the number of people to be assisted is overwhelming, but rather through group activities for women, teenagers and others.

"We try to give them tools so they can cope with this situation in the best way possible," says this medicine man from Ronda. However, it's not only the victims of war who need psychological care, but also the professionals themselves who travel to these remote places to help, along with the local people who form part of their teams. From time to time, it helps to disconnect: as José Sánchez has done, who has returned to Malaga, albeit only for Christmas.